My dad used to receive bottles of liquor as gifts, typically around the holidays. But as a beer drinker who eschewed hard liquor, he had no use for them. He kept them anyway, though, in a cardboard box in the basement; and as a dutiful son who didn’t want his parents’ cellar to become overly cluttered, I kindly took the entire box off their hands at some point when I was in college. There were some valuable things in there, like a bottle of Johnny Walker Black, and a couple of mysterious black bottles of cognac, which I still have.

There was also gin. A LOT of gin.

If memory serves, there were two bottles of Tanqueray and three bottles of Beefeater – two enormous ones (the square kind, with the handle) and a more manageable 750-milliliter bottle.

That might sound like a gold mine for a poor college student who enjoyed a cocktail once in a while, but there was one problem – I didn’t really care for gin. I found it to be harsh and unforgiving. And given the infrequency with which I drank it, I suddenly found myself with pretty much a lifetime supply of the stuff. Those bottles followed me through college, grad school, three new jobs, and at least six different residences.

Finally, about two years ago, I decided enough was enough – the gin had to go. And since it runs counter to my programming to simply dump usable liquor down the drain, I was going to have to get rid of it the hard way.

So I declared gin and tonic to be my official drink of the spring and summer and embarked on a boozy tour de force: A gin and tonic after work. Sometimes one before work. A gin and tonic and a good book. A gin and tonic while watching the Sox. A gin and tonic on the front porch. A gin and tonic on a midsummer night’s eve. A picnic with a thermos full of gin and tonic. Gin and tonics on the beach. A flask of gin and tonic at church (kidding! I never go to church).

Slowly, the tide began turning. Bottle after spent bottle would land in the recycling bucket with a satisfying thunk, and as the days of summer got shorter and shorter, I could see victory within my shaky grasp.

And then, a cruel and unexpected twist! A friend of mine was moving across the country and opted not to take the contents of his liquor cabinet, donating to me the remnants of his collection – which contained (you guessed it) another full bottle of Beefeater gin. And thus the spring and summer of gin and tonic stretched into the fall and, inevitably, winter of gin and tonic.

Gin was one stubborn bastard, as I learned; but so was I. And then a funny thing happened – I actually started liking the stuff. That harsh, piney liquor that initially reminded me of a cleaning product gradually revealed its merits, and eventually we put aside our differences.

Of course, learning to appreciate gin is a lot easier when you submit to the talents of creative bartenders who skillfully mix it into things other than just tonic water. And as I sampled drinks like the Tres Curieux at Marliave, the luscious Greed at Church, and the Vesper Martini at the Gaff, among many others, I noticed they weren’t made with Beefeater, or Tanqueray, or even Bombay Sapphire. It seemed the gin of choice among Boston’s best mixologists was Hendrick’s.

So I started asking for Hendrick’s in my drinks when given the opportunity, and while I’m no gin aficionado, I could tell there was something different about it. It seemed gentler and more approachable than other gin brands. Turns out there’s actually a lot about this gin that distinguishes it from its peers – as I learned a few weeks ago, when I attended a Hendrick’s-sponsored “Cocktail Academy.”

Hendrick’s is a small batch gin made by William Grant & Sons, the same distillers that own Tullamore Dew, among other fine intoxicating liquors. Their gin-soaked road show, the Cocktail Academy, has been stopping in major U.S. cities over the past couple of years as part of William Grant’s aggressive American marketing campaign. It’s a way to spread the word about Hendrick’s while teaching attendees to whip up a few gin-based cocktails under the tutelage of a Hendrick’s brand ambassador.

“Timeless Tipples Worth Toasting” was the subject of the Cocktail Academy’s third stop in the Boston area, led by an affable brand ambassador named Jim Ryan. Held at Catalyst, a very cool bar in Cambridge’s Kendall Square, the event was a laid-back clinic in gin mixology.

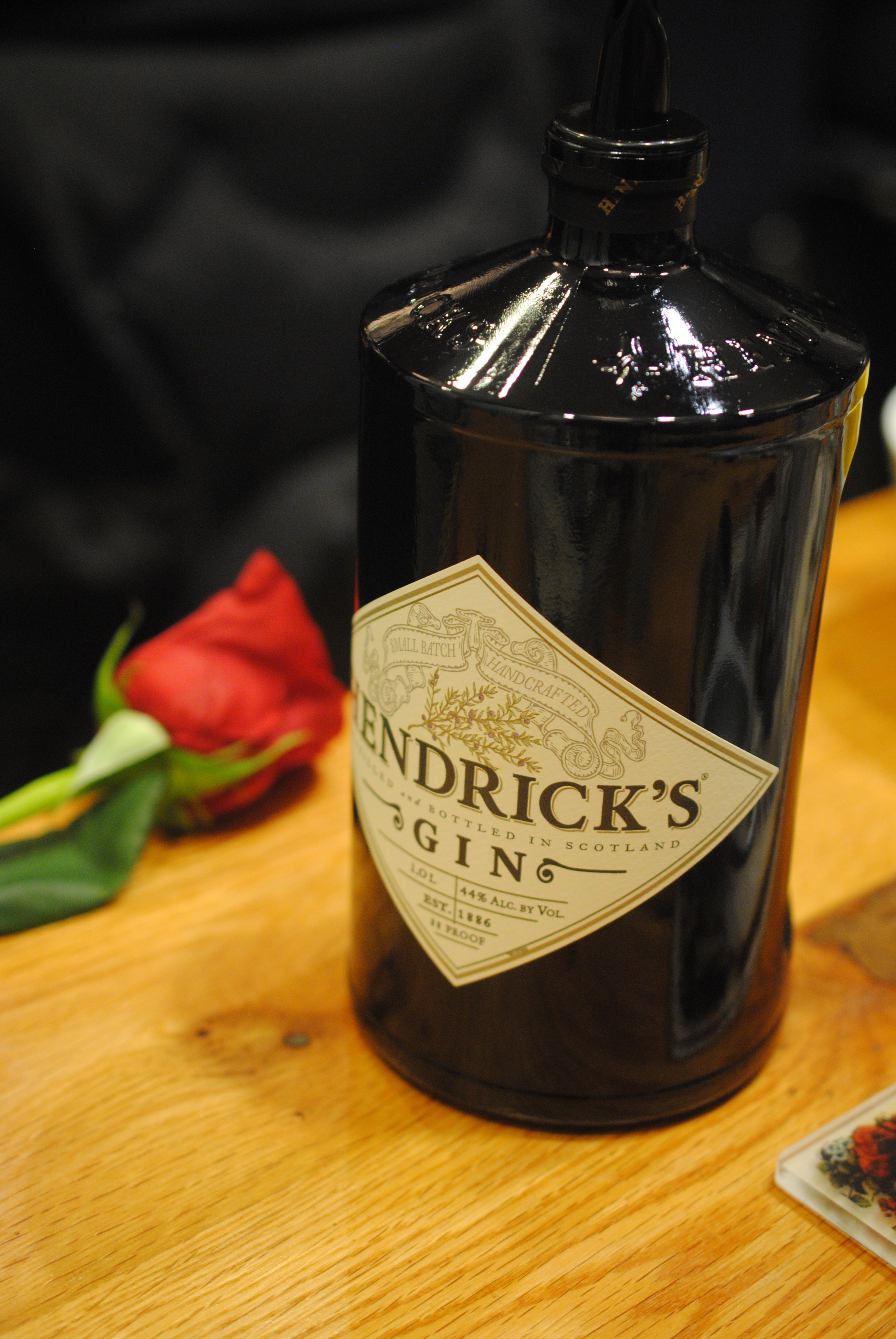

About 20 of us settled into a conference room with long wooden tables, each with place settings outfitted with all the supplies we’d need – a lemon press, weighted spoon, jigger, two Collins glasses, and a tumbler; lemons and cucumbers; simple syrup, soda, green tea, and elderflower liqueur (aka St. Germain); and of course, a bottle of Hendrick’s gin. There was also a helm full of ice. Yes, a helm.

As we settled in with passed hors d’oeuvres and complimentary gin and tonics (any class that starts off with a free drink is going to be a good one, regardless of the subject matter), Jim regaled us with the history of Hendrick’s and, more importantly, what makes it such a unique spirit, from its botanical signature – a chorus of 11 different fruits, roots, and flowers – to its distillation in two separate stills, to its pièce de résistance: an infusion of cucumber and rose petals.

It seems only fitting that an exceptional gin should emerge from such unusual origins. Hendrick’s is one of the only gin distilleries in Scotland. It’s housed in a converted WWI-era munitions factory that the William Grant company purchased in 1960s, around the same time that it bought two very rare stills. The first, made of a thick copper, is a traditional pot still built in 1860 by Bennet, Sons & Shears. The second is called a Carter-Head still, built in 1948; only a few are known to exist in the world.

Now, why purchase two antique stills? To show off in front of all the other gin distillers? Maybe; but after the stills were restored to proper working order, they both came to play key roles in the production of Hendrick’s Gin.

The stills yield two dramatically different spirits. In the Bennet still, botanicals are added to the liquid and boiled, producing an oily, concentrated gin distillate with a rich, robust flavor. In the Carter-Head, by contrast, the distillers place the botanicals in a basket at the top of this still, through which the alcohol vapors pass, extracting the sweeter and more delicate essences of the flowers and roots. Hendrick’s then combines the spirits produced by both stills, which is pretty much unheard of.

The result is a gin with an entirely unique flavor profile. It seems softer than other gins, yet more complex; that’s on account of its unusual botanical signature. While most gins incorporate a handful of fruits and flowers, Hendrick’s loads up with a whopping 11 botanicals – lemon peel, orange peel, coriander, chamomile, juniper, Angelica root, cubeb berry, elderflower, meadowsweet, caraway seeds, and Orris root. The exact proportions are a closely guarded secret known only to three or four people, but it’s clear that the juniper – a necessary component any gin, and the ingredient responsible for gin’s distinctive pine-like taste – is dialed back a bit. That alone might make Hendrick’s a bit more accessible to someone wary of gin.

But wait, there’s more! Once it’s all distilled, cucumber and rose petals are added, giving Hendrick’s a remarkably fresh flavor up front. This is why a cucumber is preferred to the more traditional citrus as a garnish for Hendrick’s-based drinks.

As the history lesson drew to a close, it was time to learn how to make some cocktails. First up was an elderflower cooler – gin, elderflower liqueur, simple syrup, and soda, served in a Collins glass. Essentially a St. Germain cocktail made with Hendrick’s in place of champagne, this was crisp, light, and summery. St. Germain plays very well with Hendrick’s, since elderflower is one of the botanicals used in the distillation process, and the brightness of the flavor balanced the dryness of the gin. Our class may have been taking place on a cold December evening, but sipping the elderflower cooler gave me visions of relaxing on my front porch on a June evening.

My warm-weather reverie continued with the next cocktail. Even before we made them, the cucumber lemonade sounded like a heavenly match – the cool, refreshing flavor of cucumber and the zing of a lemon. The recipe called for gin, the juice of one lemon, simple syrup, soda, and a long slice of cucumber, with an optional lemon garnish. Sure enough, it was a dry, refreshing cocktail with just enough sweetness and a only slight tartness. The lemon juice activated the lemon peel in the gin, and the resulting flavor, complemented by the cucumber, was strong but not overpowering.

The last drink was called a tenured punch, and this was a group project. Jim explained to us that, a couple centuries ago, punch preceded the notion of a single-serving cocktail. It was very communal; having a punch with guests meant you were sharing an experience. In that sense, it was an appropriate way to round out the class; there’s no “gin” in team, but there was only one punch bowl per table, and everyone at the table had to work together to make the punch.

We threw pretty much everything we had in there – gin, lemon juice, simple syrup, sparkling water, green tea, Lillet Blanc, Angostura bitters, and cucumber and lemon slices as garnishes, all poured over a massive block of ice. The tea was the most interesting component; according to Jim, it “stretches” the punch out, helping you avoid overpouring the liquors.

I don’t know about you, but when I think about punch, I imagine something overly fruity, loaded up with cheap liquors and bunch of mixers. The Hendrick’s tenured punch challenged that notion, to say the least. I would call it a rather dignified punch, the pinnacle of knowing how good flavors mix in large quantities as opposed to haphazardly pouring a bunch of ingredients into a bowl and giggling about how much alcohol you put in (I mean, not that I’ve ever…).

What’s more, no individual component of the punch was particularly obvious; I couldn’t really taste the tea, nor did the citrus or even the gin stand out. The flavor was truly greater than the sum of its parts.

The only disappointment of the night was discovering that the table of Hendrick’s gift bags did not, in fact, contain complimentary bottles of Hendrick’s.

But the mere fact that I would have welcomed a full bottle of gin made me realize how far I’d come from my earlier skepticism of the spirit. And that’s exactly the kind of epiphany that the Hendrick’s people would like everyone to have. While gin distilleries aren’t exactly hurting for cash, gin doesn’t enjoy anything close to the global sales of other spirits, like vodka or whiskey. Vodka, for instance, is eminently marketable; with its neutral flavor, it can be mixed with just about anything, and distilleries can appeal to younger drinkers with products like Swedish Fish or Whipped Cream flavored vodka (and yes, both exist). It’s harder to portray gin as the life of the party; it tends to be seen as a stuffy liquor, something preferred by an older crowd.

William Grant is fighting that perception, trying to broaden gin’s appeal and put it in the cocktails and liquor cabinets of a younger population. So they designed a wildly colorful website and host events like the Cocktail Academy at trendy bars, trying to show people that the range of gin drinks is considerably broader than just martinis and gin and tonics. In other words, gin can party with the best of ‘em.

It even looks cooler than other gins. The Hendrick’s bottle, wide and round, is modeled after an old apothecary jar, hearkening back to the days when gin was used medicinally. During the class, Jim joked that Hendrick’s designed the bottle to make it as difficult as possible for a bartender to pour. (Somewhere, a bartender is not laughing at this.)

Of course, all the clever marketing in the world would be wasted if the product wasn’t up to snuff, but that’s not an issue here. Hendrick’s has taken home a plethora of awards over the past 10 years, even being declared the “Best Gin in the World” by the Wall Street Journal. And while you’ll never see a bubble gum-flavored gin on a store shelf (thank GOD), Hendrick’s manages to give the spirit as much of as twist as possible with its cucumber and rose infusion.

Maybe a gin purist would quibble with the softer complexion of Hendrick’s or the post-distillation flavoring (which renders it not a “London dry gin” but a “distilled gin”; oh, the humanity). But appealing to a new audience of drinkers requires a little innovation and a lot of fresh thinking. Hendrick’s employs both to great effect, and the result is a surprisingly approachable gin that can respectably stand among the classics.

In other words, an old spirit for a new generation.

* * * * * * * * * * * * *

Copyright © Boston BarHopper. All Rights Reserved.